Investigation Best Practices

July 1, 2017

Consider the following: Imagine you got a call from a colleague who is the Audit Director at Almost Anywhere University. She is looking for guidance on a theft at their university. Her shop got a call from parking operations to let her know they had discovered that cash had been stolen from deposits on a regular basis for the past few months. Parking operations was not requesting Internal Audit assistance, just informing them they had already performed their own internal investigation. During the conversation with parking operations, it became apparent to the Audit Director that while parking operations may have had good intentions, they may not have performed their investigation properly. Parking operations felt they knew who had stolen the cash, but this conclusion was based on interview notes containing conjecture statements and opinions of the staff as to who might have taken the money. This approach created challenges for Almost Anywhere University, and this article will address a better approach to conducting an investigation.

The person that possesses the most knowledge of how to perform an investigation and has the skills to conduct and manage an investigation should be assigned to investigate.

So, how do we assist in preventing the issue above from Almost Anywhere University from happening on our campus?

ACUA’s Best Practices Fraud sub-committee surveyed ACUA’s membership to gather best practices relating to investigations. Surveys were received from 79 public and private universities of varying sizes, and the following information was compiled from the surveys and can be used to help enhance your investigation process.

DETERMINE WHO WILL COMPLETE THE INVESTIGATION

At most universities, multiple parties are involved in conducting investigations. Depending on the investigation, work may be completed by Internal Audit or another campus unit such as Human Resources, Student Affairs, Police/Public Safety, or Legal. For 44% of survey respondents, fraud investigations are handled solely by the Chief Audit Executive. For other audit shops, work is either completed by a dedicated investigator/fraud auditor (34%) or assigned to an available auditor who is not an investigator/fraud auditor (37%). Investigations are outsourced/co-sourced with a third party by 13% of survey respondents. (Note: Survey respondents were allowed to check all applicable answers, resulting in a total response greater than 100%).

Technical knowledge is important, and 33% of survey respondents require individuals working on investigations to have fraud or specialized training and 22% require the individuals working on investigations to be Certified Fraud Examiners.

So, who is the most appropriate person to assign to the investigation?

The person that possesses the most knowledge of how to perform an investigation and has the skills to conduct and manage an investigation should be assigned to investigate. It is also important for the person performing the investigation to have a working relationship with local authorities, your attorney general, or the individual(s) on campus who work most closely with them.

DETERMINE WHAT INFORMATION WILL BE COMMUNICATED AND WHEN

As with any engagement, it’s helpful to establish communication protocols at the beginning of an investigation so that all parties know what to expect and when. Of the survey respondents, 61% have standard procedures for notifying campus administration at the beginning of an investigation. The most frequently notified parties are Legal, the President/Chancellor, Human Resources, and the Vice President/Vice Chancellor of the area reviewed (unless that individual could potentially be involved in the allegations). The Chair of the Audit Committee or governing board is also often involved in the initial notifications. Some universities are also required to alert Campus Police/Public Safety, state auditors, and other state agencies of the pending investigation.

A little over one third (35%) of survey respondents are required to provide update reports during investigations, and many others noted that while not required, they often provide updates. For many, the interim reports are provided verbally.

At the end of the investigation, the type of communication largely depends on whether the allegations had merit. 52% of respondents provide “no merit” reports or notifications to the affected unit. For allegations with merit, most campuses release several different types of reports depending on the investigation including internal controls recommendations, referrals to law enforcement, and administrative action reports outlining policy violations. However, it is important to note that if there are potential prosecutorial issues you should communicate with the appropriate authorities BEFORE releasing any information concerning that investigation.

What is your communication plan for the investigation?

Consider your communication plan based on the information available at the beginning of the investigation and update the plan according to the path that the investigation leads you through.

DETERMINE THE BEST TECHNIQUES FOR CONDUCTING YOUR INVESTIGATION

While largely similar to the techniques used when completing more routine audit work, some special considerations should be given to the techniques used to gain information during an investigation.

Interviews

When it comes to interviewing, many survey respondents always use two people to conduct interviews (69%). 9% make audio recordings of interviews, and it’s important to note that recording laws vary by state. Nearly all (91%) of survey respondents document interview notes within the investigation workpapers.

Electronic Evidence

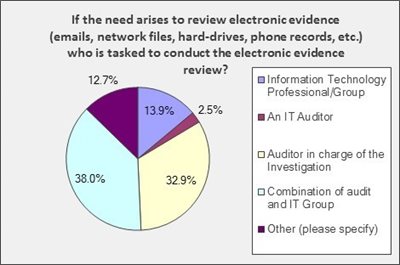

The review of electronic evidence can be cumbersome and time consuming, and more than half (52%) of survey respondents receive at least some assistance from an Information Technology (IT) group outside of Internal Audit. Several offices noted that IT may have access to tools that can help with the searching of electronic evidence.

In addition to searching university resources like email and the hard drives of university computers, many Internal Audit shops utilize Google, social media, and other internet resources such as Lexis Nexis, public property records, directory information, and state business filings when conducting investigations.

So how will my audit shop conduct an investigation?

At the beginning of the investigation, determine which techniques will be most beneficial based on the information needed to determine the validity of the allegations. Consider expanding traditional audit techniques, collaborate with other campus departments such as IT, and utilize non-traditional electronic sources of information.

CHAIN OF CUSTODY

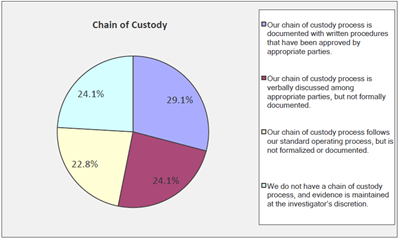

One of the key processes to be addressed in any investigation is maintaining Chain of Custody of any evidence to be used in legal proceedings. Chain of Custody is a process by which the purity of the evidence can be proven. The process ensures that there has been no alteration to the evidence being presented. The levelof formalization of the Chain of Custody process varies between Internal Audit functions, and it is important to work with all appropriate parties to establish a process that can be used in legal proceedings.

DETERMINE WHO CAN ACCESS INVESTIGATION WORKPAPERS

Of the survey respondents, 75% compile and store their investigation workpaper

s in the same manner as other audit workpapers. The remaining respondents typically use additional protection for investigation workpapers, storing them securely electronically (often in encrypted files) or physically in locked cabinets and drawers. It was also noted that workpapers may need to be documented differently if they are being prepared for use by law enforcement.

However, only 34% allow all auditors in the office to access the workpapers. 53% limit access to the team working on the investigation, and 13% limit access to just the Chief Audit Executive.

Most survey respondents restrict access to workpapers to individuals within Internal Audit, although 23% do share workpapers with other campus units. If shared, workpapers are generally shared with other departments involved in the investigation or the outcome such as Legal, Human Resources, and the Police/Public Safety. Workpapers

are also shared with senior leadership by some Internal Audit departments.

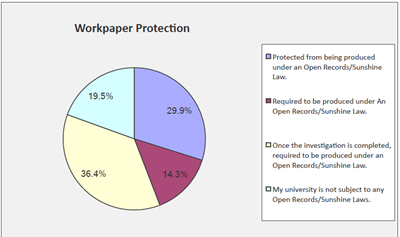

When thinking about workpapers, be sure to keep in mind public record or “sunshine” laws that may require disclosure of work. Approximately 50% of survey respondents are required to release workpapers either during the investigation or following the completion of the investigation.

What are the rules/requirements of your individual state/commonwealth or prosecuting authorities concerning access to potentially discoverable materials in court?

It is important to note and understand your local requirements, so consult with the appropriate authorities to ensure compliance with all requirements.

SO, WHAT DO I DO WITHIN MY OWN INTERNAL AUDIT SHOP FOR INVESTIGATIONS?

As you can see by the complexity of the investigative process, it is imperative to have an established and documented process for conducting investigations. Nobody wants to jeopardize the efficacy of evidence or to break the required chain of custody. To perform adequate and defensible investigations you must have a defined process for the gathering, analysis, distribution and summarization of the facts and evidence for any potential criminal/disciplinary actions. Only staff with appropriate training/credentials should be assigned the work to perform an investigation. If you are unsure about what is needed at your university, consider consulting with your legal office, governing board, and prosecutor.

In case you were wondering, the case in parking operations identified in the introduction of this article was a real case from an ACUA university. The case was taken to the Attorney General and was not defensible in a court of law because the investigation was not performed appropriately and key pieces of processes and evidence were not thoroughly investigated or documented. So, it does matter WHAT you do, WHO does it, and HOW you do it. Make sure you have a plan and ensure that your plan meets all of your university, state and federal requirements. Otherwise, your University’s legal actions may be limited.

ACUA’s Best Practices Committee would like to thank all the participating universities for their responses to the survey.

About the Authors

Craig Anderson

Craig is a Certified Fraud Examiner. He received his bachelor’s degree in computer information systems from Harding University and received his masters of science in Accounting from Harding University. Craig has over 25 years of...

Read Full Author Bio

Craig Anderson

Craig is a Certified Fraud Examiner. He received his bachelor’s degree in computer information systems from Harding University and received his masters of science in Accounting from Harding University. Craig has over 25 years of experience in various industries including financial services, biomedical processing, public accounting and higher education. His roles have spanned internal auditing, Sarbanes Oxley, risk management, business process improvement and general accounting in large sized private companies, Fortune 500 organizations and a “Big 4” public accounting firm. Craig is recognized for his skills in forensic investigations and the preparations of materials for prosecution.

Craig is an active member of the Institute of Internal Auditors and College and University Auditors of Virginia (CUAV) (previously serving as Treasurer). Craig has been an active speaker at national ACUA Conferences (2013, 2014 and 2016) and CUAV (2011, 2012 and 2013). Craig has also done presentations for local AGA and ACFE chapters.

Mr. Anderson’s areas of expertise are:

- Fraud

- Auditing NCAA Compliance

- Auditing Student Financial Aid

- Introduction to Higher Education

- Auditing Parking and Transportation Services

- Auditing School of Medicine

- Auditing School of Pharmacy

- Risk Assessment

- Auditing School of Dentistry

- Auditing School of Nursing

- Auditing Time and Leave Accounting

- General Controls for the non-IT Auditor

- Auditing Grant and Contract Accounting

caanderson@vcu.edu

Articles

Investigation Best Practices

Melissa B. Hall

Melissa Hall is the Deputy Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer at Georgia Institute of Technology. She is a Certified Public Accountant, a Certified Fraud Examiner, and a Certified Compliance and Ethics Professional. Melissa has over two...

Read Full Author Bio

Melissa B. Hall

Melissa Hall is the Deputy Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer at Georgia Institute of Technology. She is a Certified Public Accountant, a Certified Fraud Examiner, and a Certified Compliance and Ethics Professional. Melissa has over two decades experience in both internal and external audit and compliance.

Her prior experience as an audit manager with a regional accounting firm, and as the Chief Financial Officer of a K‐12 education institution, has provided her with a unique perspective and insight on fraud investigations in Higher Education. The varied background of operations and external audit provides unique insight when investigating allegations of misconduct on Campus. Her people skills are an asset when working with both internal and external legal counsel, prosecutors, and other law enforcement agencies.

Melissa is very active within the ACUA community and enjoys every minute of volunteering. The return on investment is multiplied exponentially every time.

melissa.hall@business.gatech.edu

Articles

Investigation Best Practices

Letter from the President

Letter from the President