Risks and opportunities represent the boundaries of institutional considerations. On the one hand, organizations need to guard against unwelcome possibilities that could upset carefully crafted strategies to achieve their mission objectives. Alternatively, they want to seize opportunities commensurate with their risk appetites.

Academic institutions are similar to any large enterprise in that they are susceptible to unplanned situations and “black swan” events. In today’s open environments and social media blitzes, it has never been more accurate that “rumors can travel around the world before truth can get its pants on.” Even worse, insider fraud and misconduct have tarnished many reputations in corporate and university settings. Equally so, many new developments and technological breakthroughs have been missed by institutions that have not opened their lenses wide enough to see these new opportunities.

“Managing an organization’s risks in individual silos is like trying to pick up a six- pack without the little plastic thingy that holds them together; you can do it, but it is far harder than it would be if the cans were connected to each other.”

— Andrew Bent

(Risk Management Magazine,

March 5, 2013)

To deal with these emerging situations, academic institutions of every size and scale have responded with a variety of policies and programs to stem the tide of unfortunate happenings and position themselves to take advantage of opportunities. One such initiative is the adoption of an enterprise risk management (ERM) framework, which serves to manage institutional risk issues in a systematic and integrated fashion. This is critically important to Board members and Practitioners because they are the ones charged with the oversight and implementation of risk management matters for their institutions. Clearly, this means that when something goes wrong or something is missed, they are the ones called to account by their stakeholders. Equally important is that university budgets are highly constrained and it only takes one major negative event for revenue sources to be impacted. Those institutions that cannot re-prioritize constrained budgets to allow them to seize opportunities will be left behind.

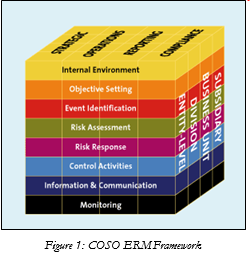

ERM frameworks first came to the forefront as a reaction to the financial improprieties in the 90s that brought down highly renowned firms such as Enron and Worldcom. Almost overnight, billions of dollars of investor savings and millions of jobs disappeared. In the United States, after exhaustive analysis and extensive new federal regulations, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the accounting and finance profession embraced guidance by a group called the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). COSO was originally founded in 1985 in response to growing corporate fraud and the passage of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in 1977. The founding group was comprised of the American Accounting Association, the Association of Certified Public Accountants, the Financial Executives International, the Institute of Management Accountants, and the Institute of Internal Auditors. They set forth a charter to study causal factors leading to fraudulent financial reporting and published Internal Controls—Integrated Framework as a compliance tool for public companies in 1992. Going further due to continued financial irregularities, they released Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework in 2004. As can be seen in the COSO Cube representation in Figure 1, the COSO ERM Framework provides a three-dimensional perspective of an integrated approach to risk categories (top side of the cube), risk management components, or activities (front side of the cube), and organizational levels of the institution (side of the cube). The idea is to identify and evaluate risks at all organization levels and in all risk categories in an integrated fashion.

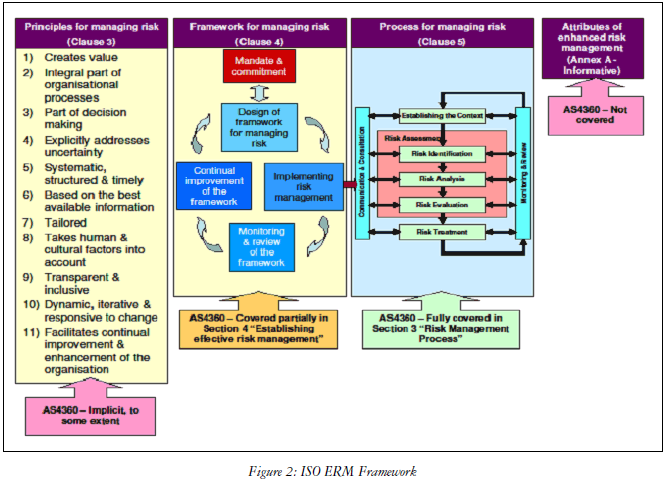

A 2015 analysis by consulting firm Protiviti indicated 75% of US public companies have adopted the COSO Framework, but this has not been the case for US institutions of higher education. Many universities that have implemented the COSO ERM Framework have found it necessary to modify it to fit their academic environments. As a result of the 2008 global financial crisis, the United Kingdom and its financial institutions decided that a more standard and repeatable approach should be applied to their commercial enterprises and drove the foundation of a quality standard for institutional risk management. In 2009, ISO 31000 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines was published by the International Standards Organization (ISO). Given the general acceptance of ISO standards in Europe and the former British Commonwealth, ISO 31000 was quickly adopted in those countries and is progressively being adopted by many countries outside the United States. As noted in Figure 2, the

ISO 31000 ERM Framework utilizes a two-dimensional representation of the principles, the flow, the mechanisms, and the attributes of a typical risk management system.

Here again, not many higher education institutions have formally adopted the ISO 31000 ERM.

Framework. In general, those academic institutions that have been aggressive in the use of quality standards and formal management systems have been the ones to implement the ISO 31000 ERM Framework. However, there appears to be reluctance in academia to utilize any ERM framework that has its origins in industry. This is possibly attributed to a prevalent feeling that industry solutions and applications are overly prescriptive and insufficiently flexible to work in academic environments where controls and authority are often highly autonomous and decentralized.

A third framework, the

University ERM Framework, was devised for an academic environment as a result of Figueroa’s 2016 dissertation on university risk management systems. This framework was developed to provide a mechanism tailored to a university organization structure. It contains more flexibility suitable for an academic culture and it includes more risk management dimensions than the COSO and ISO frameworks. It is based upon a set of principles including the promotion of integrity and ethical conduct, linkage to the strategic objectives of the institution, and the encouragement of vertical and horizontal communications. Flexibility and allowance for uniqueness of approaches within the academic institution were paramount in the development of this university model. There are five dimensions in the University ERM Framework: (1) the accountability dimension with two distinct chains (administrative and academic), (2) the independent risk category dimension, (3) the time horizon dimension, (4) the risk severity dimension, and (5) the risk response dimension with hard linkage to strategic objectives. The concept is to use the components of the five dimensions in an integrated, yet flexible manner to allow university functions and departments to maintain their autonomy in developing their individual risks, and yet enable the integration of the most critical risks across the institution.

As can be seen in Figure 3, each of the university accountability levels on the left hand side evaluates their risks within the constructs of risk categories, time horizons and severity levels. They utilize the risk response processes on the right side of Figure 3 to identify their most critical risks. Board members, for example, would tend to identify risks that address institutional viability, 20 to 50 year time horizons, and severe to catastrophic consequences. A Department Chair, on the other hand, would likely focus on risks associated with academics, finance and budget, a 1 to 5 year time horizon, and moderate to serious consequences. An annual process would solicit the most critical risks from each of the accountability levels and then a selection process would pick those deemed most critical to the institution as a whole.

After risk mitigations and resolutions are implemented, results would be evaluated after an appropriate time period and the cycle would begin again. Clearly, there would be changes and modifications from time period to time period, based on prior year results and the dynamic environment facing a typical academic institution.

SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES OF THE ERM FRAMEWORKS

Each of the models described are principle-based and allow for flexibility in their application to an academic institution. The COSO and ISO ERM Frameworks enjoy a great deal of acceptance in corporate and industrial enterprises, but have not achieved that same level of adoption within institutions of higher education. Often, in universities that have adopted one of these two models, some modification was made to fit the culture and tendencies of the institutions. The University ERM Framework offers an alternative approach to enhance flexibility and expanded dimensions, but has not yet been implemented by an institution.

RECENT RESEARCH

A 2016 research dissertation by Figueroa discovered that enterprise risk management has not been embraced by the great majority of universities. The research targeted 50 US public research universities that met the criteria of being doctoral-granting research universities, were classified by the Carnegie Foundation as Highest Research Activity institutions, had at least 20,000 students, and were affiliated with a medical facility. Twenty-two of these 50 top-tier public research universities participated in the research. Only eight of the twenty-two universities included in the research have adopted ERM approaches and frameworks. Only six of the twenty-two utilized a risk management process to roll up risk assessment results to an institutional level, despite the prevailing views that it is an effective approach to “connect the dots” of risks and opportunities and prevent losses of life, property and reputation.

One result of this limited use of ERM frameworks to manage risk is that fewer than half (41%) of these twenty-two top-tier public research universities conducted institutional risk discussions at their governance board meetings. Similar results were noted at the university administrative level where the same percentage included institutional risk discussions as part of their upper level management meetings.

This hesitancy to embrace enterprise risk management was reflected in the lack of linkage of risk management to the institution’s aspirations and strategic objectives. Few of the twenty-two universities explicitly included risk and opportunity as part of the formal strategic planning cycle. Even fewer of the twenty-two expressed their risk management intentions and strategies in their formal policies and procedures.

This lack of formality in the institution’s risk management policies and procedures creates a fragility and lack of sustainability when adversity strikes or when there is a change in leadership. Several seemingly robust enterprise risk management programs at these twenty-two top-tier public research universities have seen these initiatives languish or go into hiatus when a new leadership team takes its place at the helm.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

Following are two examples that help illustrate the ways higher education institutions have implemented the COSO and ISO 31000 ERM Frameworks in academic environments.

INDIANA UNIVERSITY

Indiana University’s journey with ERM began officially in 2012. At the time, several members of the Indiana University (IU) Board of Trustees were executives in local corporations that had implemented ERM over the previous decade. These members had repeatedly requested IU to pursue the creation of an ERM program, due to their positive experiences in their own organizations. The COSO ERM Framework was selected for Indiana University because several of the Board members were familiar with the COSO ERM Framework; the university’s Internal Auditors were familiar with the companion COSO Internal Control Framework; and a variety of resources was available from the consultant and business world on how to implement an ERM program using the COSO materials. The COSO ERM Framework was seen as a guide to creating an overarching structure that would allow university executives to address the highest risks and opportunities to the mission and enterprise strategies and objectives, while also allowing business sectors of the university to continue to use the best risk management tools for their professions for managing business unit risks and opportunities. Risk owners could easily elevate to the ERM process any risks they identified in their own areas that affected the overall university’s objectives.

The COSO ERM Framework states “Enterprise risk management is not strictly a serial process, where one component affects only the next. It is a multidirectional, iterative process in which almost any component can and does influence another.” IU did not begin by working sequentially on each component of the COSO cube. Instead, leaders analyzed what value they wanted out of the process, and determined which pieces worked best for the institution at its beginning stages of implementation.

From the front side of the COSO cube in Figure 1, IU decided to implement as many components as possible, since these eight components lay a foundation for a fully mature risk management program. However, some components (Objective Setting, Event Identification, Risk Assessment, Risk Response, and Monitoring) have been implemented in more depth than others (Internal Environment, Control Activities, and Information and Communication).

As for the top side of the cube, IU tailored the COSO objectives categories to fit its higher education environment. Instead of strategic, operational, reporting, and compliance, IU used strategic, operational, financial, compliance, and reputational. While well aware of the controversy around calling reputational risk an objective category (many insist reputation is instead a result of a risk occurrence), IU executives ultimately decided to make it a category because reputation, through accreditation, ratings, government statistics, and other types of reviews, is so key to success or failure in higher education. It was important to ensure that Risk Owners distinctly considered and analyzed this category of risk at the enterprise level.

Finally, for the right side of the COSO cube, IU has so far focused efforts almost exclusively at the entity level. This limitation has allowed the institution to get started with fewer resources, to leverage risk management work already being done throughout the organization, and to focus on the most important enterprise risks and opportunities. The ERM program has occasionally made its way down to the division level, for example, if a failure by a division could truly bring down the entire university. A good illustration of such a division in a university setting is a key school that brings in a disproportionate proportion of overall revenue, such as a School of Medicine. IU’s ERM program also addressed the subsidiary level, but did so by defining it as the risks of our contracted third parties or “affiliated organizations,” and by making it a Risk Area of its own. Indiana University has not yet considered taking the ERM program efforts down to the business unit level. Thus, so far it has been solely a “top-down” approach, in which executive management identifies the major risks and opportunities to the organization.

In 2012, the Board approved an initial ERM program structure, including roles and responsibilities, and following the COSO ERM Framework. An Enterprise Risk Management Committee (ERMC) comprised of members of the university’s executive team began meeting monthly. First, the ERMC identified eighteen business functions, or Risk Areas, that had to be operating well in order for IU to be able to achieve its mission and strategic objectives, and assigned Risk Owners to each Risk Area. A list of these Risk Areas is provided in Figure 4. Risk Owners typically are at the Vice President or Director level.

Each Risk Owner goes through a ninety minute facilitated risk identification process with the Chief Risk Officer to identify that area’s top three to five enterprise risks – those risks that could keep IU from achieving its enterprise mission and key objectives. Risk Owners outline those risks in a template report document, including their assessment of likelihood and impact and a description of past, current, and desired future mitigations. Each Risk Owner then attends an ERMC meeting to discuss his or her report. These one-hour discussions of the ERMC with each Risk Owner have been the most valuable part of the ERM implementation so far. Not only are risks and the effectiveness of mitigations discussed, but many times, these risk conversations evolve into dialogues about the possibility of turning those risks into opportunities.

The discussion results in one or more of three possible actions:

- The ERMC accepts the Risk Owner’s report as an accurate representation of the risks and as having an appropriate level of mitigation for each risk.

- The ERMC decides to monitor one or more of the risks. This usually is for situations where there are planned mitigations, but they are still in process or not yet begun. The Risk Owner is to report back at intervals about the progress and effectiveness of the mitigations.

- The ERMC asks for additional risks to be included, additional actions to occur or a different viewpoint to be considered. This is often in situations where the risk needs multiple business functions to work together, which the ERMC calls cross-functional risks. In such cases, the Chief Risk Officer or the Chief Compliance Officer brings together the appropriate experts to analyze the issue and propose a plan back to the ERMC. Upon acceptance of the plan, the action moves to the monitoring stage. In some cases, Risk Owners have been asked to look at the risk from a different viewpoint, causing mitigation plans to be re-evaluated in order to transform the risk into an opportunity.

After reviewing all eighteen Risk Areas, the ERMC rates all of the compiled risks on likelihood and on six severity of impact measures, and choses Key Enterprise Risks to focus attention on in the coming year. Among other forms of analysis, these Key Enterprise Risks are mapped to the current institutional Strategic Plan, and groups of Subject Matter Experts are convened to do Bow Tie Analyses to brainstorm possible causes, consequences, and mitigations. All those who participate in some way in the ERM

process also receive a monthly environmental scan publication, to help them stay abreast of trends and emerging risks and opportunities that could impact IU going forward. This increase in risk and trend awareness improves both short-term and long-term decision-making.

Reports to the Board of Trustees were given more often in the beginning years of the program, but there is always at least a required annual report. In addition, Internal Audit leverages the ERM data in their annual risk assessment process used to create the audit plan for the next year, and they ensure that annual audit plans are covering the breadth of the ERM Risk Areas, including any ERM risk mitigation plans that have recently been completed. Many times, Risk Owners are able to use the results of this annual Internal Audit risk assessment to populate their ERM report – at least for those risks that are auditable. Risk Owners are also prompted during the ERM process to include non-auditable risks (generally the reputational and strategic risks) in their ERM assessment. In addition, Internal Audit has changed their Board reporting format to match ERM terminology and Risk Areas.

The structure of the IU ERM process is illustrated in Figure 5.

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA

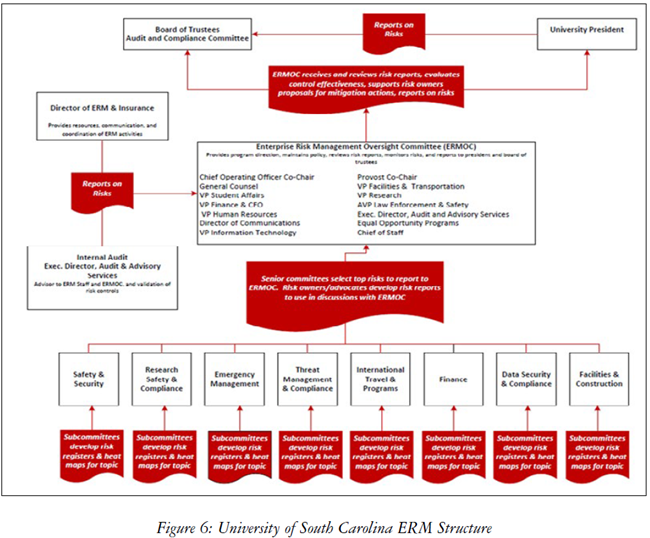

In an effort to comprehensively manage risks faced by the University of South Carolina (USC), a collaborative Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) program was implemented using the principles and guidelines found in International Standards Organization (ISO) 31000-2009. ISO describes risk as the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”, which can be positive and/or negative. The initial stages of implementation began in late 2013 and focused on three main objectives:

- Developing an organizational structure to support the ERM process.

- Utilizing existing committees to streamline implementation.

- Involving individuals from all levels of the organization.

These objectives were accomplished by adopting a combined “top-down” and “bottom-up” methodology in the organizational structure used to identify, evaluate, control and monitor major organizational risks and opportunities. A bottom-up approach can be described as identifying risks “at all levels of the organization in an attempt to provide as complete a picture as possible of all the organizations’ risks.” The top-down approach is described as “senior management, along with its board of directors, identifies major risks to the organization.” In order to support a combined methodology, the University developed a robust ERM committee organizational structure intended to provide representation of key risk owners and stakeholders from all levels of the organization.

At the University of South Carolina, an ERM Executive Oversight Committee (EOC) ensures a “top- down” approach in identifying, assessing, controlling and monitoring significant organizational risks and opportunities. This committee is comprised of senior leadership and is responsible for maintaining the ERM policy, providing direction for program implementation, identifying major areas of risk and opportunity, reviewing risk data submitted by subcommittees, monitoring, reporting, and discussing risk information with the University President and Board of Trustees. In an effort to streamline and provide direction to the ERM implementation process, the EOC adopted a listing of “high priority risk areas” previously complied by the University’s Audit and Advisory Services department. This risk listing was compiled by interviewing the president, board members, and senior leadership in an effort to determine what risks they believed could have the biggest impact on the institution.

“An effective institutional or enterprise risk management (ERM) program, with the full support and engagement of the governing board, will increase a college, university, or systems likelihood of achieving its plans, increases transparency, and allow better allocation of scarce resources. Good risk management is good governance.”

—Association of Governing Boards

Generally, the high priority risk areas identified by senior leadership have been broad in nature. In an effort to provide the EOC with more detailed risk information about the identified high priority areas, the ERM program utilized lower level subcommittees to identify additional risks and opportunities, assess risks and controls, and to develop associated risk monitoring and measurement data. Lower level subcommittees ensure a “bottom-up” approach to risk identification, assessment and control. These subcommittees are generally responsible for management or oversight of specific risks. Risk information collected by these subcommittees is reviewed by the EOC in an effort to gain additional insight into the broad high priority risk areas. There are currently thirty-five subcommittees involved in the ERM process, the majority of which existed prior to initial ERM program implementation. These committees have representation from over 100 different University units, external stakeholders, and over 200 different individuals are involved to some extent in the ERM process. In an effort to provide a more holistic view of the risks facing the institution, additional subcommittees are continuously brought into the ERM structure and process.

ERM program implementation had the immediate benefits of improving organizational learning and increasing awareness about the need to identify and treat risk throughout the entire organization. These benefits were realized through implementation of a risk management training program that not only edu- cated University personnel about the basic concepts of identifying, assessing, treating and monitoring risks, but also increased organizational awareness of the high priority risk areas identified by senior leadership.

As can be seen, the combined top-down and bottom up approach to ERM “…can identify significant risks, provide a global risk perspective, provide a top level view of risks, improve the University’s risk culture, and allow a prioritization of identified risks.” This approach can also be used to enhance communication between internal and external risk owners and stakeholders by involving individuals from outside the organization.

BENEFITS AND DRAWBACKS OF THE ERM FRAMEWORKS

An ERM framework is a standard structure that can guide the development of a new program, pull together existing risk management activities into a coordinated program, provide a tool to assess the maturity of a program, or frame an audit of a program. An ERM framework can help ensure that all institutional risk and opportunity activities are coordinated together to paint a whole picture, including all aspects of risk and not just those that are insurable, and including the upsides as well as the downsides of risks. It can help clarify the types of risks (i.e., strategic, financial, operational, and compliance) that an organization faces. It can especially help illuminate the interconnections between risks among and between different business function silos, identify shared root causes, and prioritize one business function’s risks against other business function risks. Most importantly, ERM frameworks provide a structure that, if implemented well, increases the likelihood of the organization achieving its mission and objectives, which in turn can improve stakeholder confidence and trust. Improved decision-making and organizational resilience are key benefits of the successful implementation of an ERM framework.

The fact that the three ERM frameworks presented in this paper do not provide specific details on how to implement an ERM program is both a benefit and a drawback. They are not how-to manuals for conducting risk management activities – they expect that the user already has basic risk management knowledge and business expertise. Instead, they describe what an effective process looks like and what principles and components are involved. The generic nature of the standards allows organizations the freedom to develop and implement an ERM program that is readily acceptable, functional, and tailored to the institution.

However, lack of specific implementation details can often leave implementers unsure if their programs truly conform to the framework. Can an institution say it has implemented COSO or ISO if they have not implemented all of the components? What if the organization implemented all of the components, but renamed some of the framework’s terminology to fit the organization’s culture? Are the specific risk management tools and techniques chosen by the institution to implement those components considered acceptable? While the high-level nature of the frameworks is a benefit when it allows the institution flexibility in implementation, it also is a drawback in that the organization must invest time and effort into designing that implementation’s details.

Further, academic culture can be skeptical or even antagonistic to applying “business” approaches such as COSO and ISO to a higher education setting. Some believe if it works for business, it cannot work for higher education. Some even hold the erroneous view that COSO and ISO can only be used in private industry and manufacturing. It is true that most examples in the literature, in the frameworks themselves, and at conference presentations are from the business world. This illustrates the lack of knowledge about the ways in which these frameworks can be implemented in the very complex and diverse higher education environment.

BOARD MEMBER IMPLICATIONS

Board members of institutions of higher education are central to the successful establishment and deployment of risk management programs. More and more, they are being called to account for their governance role overseeing the administration and operations of a university and its many components. As a result, Board members need to know and understand risk management tools and techniques and how they are applied to the institutions that they oversee. In addition, every framework emphasizes that the right “tone from the top” is absolutely essential to the successful implementation of the framework.

While it is possible for Board members to oversee domain-specific risks and opportunities independently, the use of an ERM framework allows the Board member to understand risk and opportunity in the context of the institution’s mission and objectives. It broadens risk management activities beyond the

financial and insurable risks, and beyond loss prevention and compliance. It extends the risk management scope to include opportunities. It encompasses a strategic view at the enterprise-wide level. It helps avoid spending Board member’s time on the risks down “in the weeds,” instead keeping the level of involvement at the strategic and governance level. And, it causes the Board’s oversight to focus on the highest enterprise risks overall – the ones most important for Board members to keep an eye on.

Finally, without Board and executive level engagement in the risk management program, without that “tone from the top,” it is very difficult for an institution to obtain a high level of maturity in its risk management activities. While some pockets within the organization may do well handling risks and opportunities for their business function, other pockets, without a charge from the top to engage in proper risk management activities, will not do so. There is just too much to do, and too few resources. A Board and executive-led ERM program will identify the highest risks to the institution – the ones that absolutely must be well mitigated – and will cause action throughout the organization by their engagement in the ERM program.

PRACTITIONER IMPLICATIONS

Risk Owners and management personnel make day-to-day and long-range decisions based on risk as a normal part of business. Many use tools specific to their profession to conduct risk assessments and manage their business unit’s risks and opportunities. This “bottom-up” risk management process is standard and expected. However, without the use of an ERM framework to create a “top-down” process involving the Board and executive management, those unit-level risks rarely have the opportunity to be compared across business silos and to be “raised up” to be discussed as possible enterprise risks. Participation in an ERM program allows all participants to understand risk in the context of the institution’s mission and objectives, to recognize the interconnections between risks among and between different business function silos, to identify shared root causes, and to collaborate on mitigating risks and seizing opportunities.

Implementing an ERM framework in a higher education institution will transition existing risk management activities from their traditional focus on only insurance and insurable risks to a broader and more holistic consideration of all types of risks facing the university. Risk Owners and managers across the institution will increase involvement and contact with the ERM leader and other Risk Owners and stakeholders, and gain a better understanding of the broader range of risks facing the institution. An ERM program will introduce the basic concepts of risk management to a much larger audience.

WHAT THE FUTURE PORTENDS

Both COSO and ISO are in the process of modifying their ERM frameworks to incorporate evolving knowledge and experience in using the platforms in a variety of institutions. At first glance, it appears that each are moving toward each other in terms of relying more on principles and less on prescriptive implementation. Neither COSO nor ISO is focused on institutions of higher education and thus may not be seen as particularly helpful to universities that are contemplating adoption of these two frameworks. However, adaptation and tailoring of these frameworks has been shown to be effective. In addition, alternative academic models such as the University ERM Framework are available for implementation. To ensure their institutions not only survive but thrive in the dynamic years ahead, Board members and practitioners must lead the effort to manage their risks and opportunities in proactive ways by using the best tools and techniques at their disposal. By understanding the benefits of an enterprise risk management framework and driving its implementation for the greater good of their universities, responsible Board members and practitioners can add lasting value to their institutions.

(References are available by contacting author Francisco Figueroa)