Human Resource Operations: Internal Controls Practices and Risks for Pre-Employment Background Checks and Overload Pay

November 12, 2020

Many institutes of higher education tout employees as being one of their greatest assets. As such, the goal of any college or university is to hire the best candidates. To achieve this goal, human resources (HR) and payroll departments play a significant role and there are several key internal controls and compliance requirements that contribute to successful hiring practices and procedures. However, HR and payroll typically rely on various institutional departments and key vendors to help safeguard hiring controls and compliance processes.

Figure 1 shows the major departments typically involved in one of the most common control processes used—pre-employment background checks.

Source: Compiled by Portland State University’s Internal Audit Office (IAO) based on benchmarking work performed during fiscal year 2017.

Pre-Employment Background Checks

Institutions operating in the United States are required, under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), to obtain written permission from applicants to acquire a background check from a third party company. Additionally, the FCRA requires the institution to provide a copy of the background check to the job applicant when an institution chooses an adverse[1] employment action based on the results disclosed. It is recommended to consult with your institution’s General Counsel to understand all of the legal and contractual requirements applicable to your institution’s pre-employment background check processes as certain states may have laws that require additional procedures beyond these applicable federal regulations. Finally, the FCRA requires the institution to provide the job applicant disclosures regarding the applicant’s right to appeal the results and/or take steps to correct inaccurate background check results. Given these federal requirements, internal audit may provide value by conducting a review of the institution’s FCRA compliance processes. A review may be especially valuable if multiple departments are permitted to run pre-employment background checks.

Background Check Policy and Industry Practices

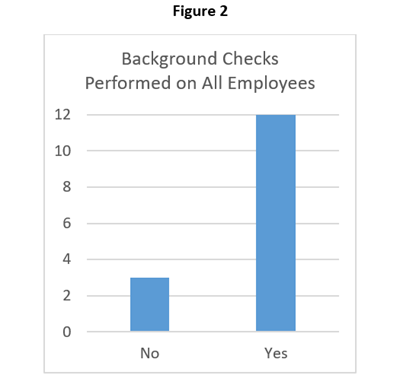

The Portland State University Internal Audit Office (IAO) conducted an audit focused on background check controls and benchmarked industry practices for pre-employment background checks. Out of 15 higher education institutions benchmarked, IAO found 12 had policies requiring background checks on every final candidate before completing the hiring process. Although the remaining three institutions did not require background checks on all new hires, they had policies for background checks on employees with duties that included working with minors, access to sensitive data or equipment, working in residence halls, access to financial systems, or the authority to approve significant financial transactions.

Source: Compiled by Portland State University’s IAO based on benchmarking work performed during fiscal year 2017. Contact the IAO for a detailed list of higher education institutions used in the benchmarking. The institutions used in the benchmarking were of similar size to Portland State University and located in a similar urban environment.

The benchmarking project identified the following additional controls used within the higher education industry:

- All employees who care for research animals undergo a background check

- Employees holding positions that deal with sensitive data, work with minors, and/or are deemed security sensitive undergo a periodic background check every three to five years

- Institutional policies requiring university affiliates[2] to run background checks on affiliate new hires

- Verifying the individual is not listed on the federal excluded parties list (i.e., sam.gov) before extending an employment offer

- Committee review of negative background results to verify whether the results impact the individual’s ability to work in the position offered or other positions at the university

- Background check policy requiring parental consent before a background check is performed on a minor

- Background check exclusions for employees rehired within 90 days to one year of separation from your institution

- Faculty background checks prior to an offer of tenure or other significant commitment to the university

Considerations When Conducting a Review of the Background Check Process

- Verify accuracy of faculty Curriculum Vitaes (CVs). Hiring institutions should ensure the accuracy of faculty CVs to avoid the risk of improper data reporting. For example, institutions hiring departments should consider verifying degrees, patent ownership, and/or authorships of publications listed on a final candidate’s CV.

- Self-audit internet pre-employment background checks. To protect against reputational damage from events not detected on federal background checks, perform an internet search to verify the applicant’s information.

- Evaluate timeliness of results and determinations. Many institutions run into a bottleneck when conducting manual background checks. Upgrading to an automated vendor solution may expedite the hiring process and give the institution a competitive edge.

- Standardize background checks. Consistent application of background checks can help mitigate the risk of discrimination in the hiring process.

- Review vendor contracts. Vendors with access to sensitive areas of campus, such as residence halls or childcare facilities, put the institution at a higher risk of regulatory noncompliance and potentially compromise the safety of those under the care of the institution. Consider reviewing custodial and food service vendor contracts for language requiring staff to undergo background checks prior to beginning work on campus. In addition, review vendor contracts for audit clauses allowing internal audit to review the details and results of background checks. If the contract stipulates specific criminal offenses that require university management review and approval prior to the vendor employee beginning work on campus, then consider testing controls to verify the effectiveness of risk mitigation.

Overload and Supplemental Pay

Overload and supplemental pay have the potential to become abused, especially during periods of salary or hiring freezes.

Higher education institutions may grant employees several types of supplemental compensation for activities beyond the employees’ assigned duties. The two types most frequently seen are overload and supplemental pay. An institution generally grants overload pay when faculty teaches a course, or multiple courses, in addition to their normal course load. An institution may also grant supplemental pay to employees taking on job duties beyond their current position description or for working in an interim role. Overload and supplemental pay have the potential to become abused, especially during periods of salary or hiring freezes. Therefore, an adequate internal control system is necessary to mitigate potential abuse and risks related to these types of transactions.

Controls and risks to consider during a review of this area include:

- Establish and adhere to limits on the maximum number overload credits a faculty member can teach. An accrediting body may impose limits or an institution can set caps to help support academic excellence.

- Restrict supplemental pay to no more than a set percentage of an employee’s base salary (e.g., 20%). Require higher-level reviews and approvals when supplemental pay will exceed the maximum percentage.

- Confirm the job description for the employee’s current position does not already assign the proposed supplemental job responsibilities.

- Monitor unusually high pay amounts through audit control reports. Audit control reports may identify input errors, abuse, or potential fraud.

- Implement time limits for supplemental pay (e.g., an employee may receive a maximum of up to one year of supplemental pay). Require upper management to review and approve all supplemental pay that will extend past standard termination periods.

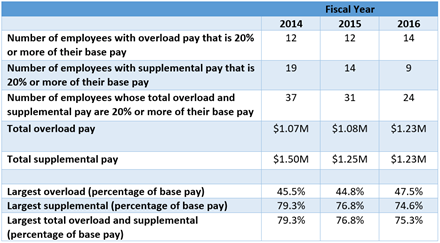

Figure 3 provides an example of the IAO’s analysis of the overload and supplemental pay over a multi-year period:

An audit or advisory project of HR and payroll operations may identify areas of excess spending and resource inefficiency.

Figure 3

Source: Compiled by Portland State University’s IAO based on benchmarking work performed during fiscal year 2017.

A risk analysis similar to the one above can provide value to internal audit when included as part of the risk assessment process to identify where to focus audit fieldwork efforts. An audit or advisory project of HR and payroll operations may identify areas of excess spending and resource inefficiency. In addition, a project in this area may help institutional management identify and manage reputational and compliance risks, as well as potential control abuses.

[1] An adverse action is a denial of employment or any other decision for employment purposes that adversely affects any current or prospective employee. In addition, notification requirements under the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act, Dodd-Frank Act, applicable state laws, and collective bargaining agreements may be required if your pre-employment background check includes running a financial credit check on applicants.

[2] University affiliates may include foundation employees, student alumni groups, and athletic booster groups.

About the Authors

Christine Croskey

Christine is a Certified Internal Auditor and has been part of Portland State University's Internal Audit Office since 2015.

Read Full Author Bio

David Terry

David Terry, CPA, CFE, CIA leads Portland State University’s Internal Audit Office. He has more than 17 years of experience in auditing and also holds positions as an audit committee member on two Oregon governmental audit committees.

Read Full Author Bio