Bull by the Horns: Conducting an Audit for Export Controls

Over the last 15 years, the academic community has made great strides in improving its understanding of the U.S. export controls regulations and building out the expertise to develop comprehensive export controls compliance programs. Now that many institutions have mature or semi-mature compliance programs, internal audit teams are being tasked with tackling this complex area of federal regulations. This article walks through the basic export controls regulations and provides insight into a U.S. government report that highlights gaps. It also provides guidance on how internal auditors can begin to think about constructing an export controls audit that is effective and comprehensive.

U.S. Export Controls Regulations: Basics and Key Elements of an Export Compliance Program

Did you know that not all “exports” leave U.S. borders? That is true if you are following the federal export controls regulations. These regulations cover sending tangible items, technical information, and software out of the U.S. and sharing it with non-U.S. Persons in the U.S. The latter is deemed to be an export to the recipient’s home country. In some cases, the export controls regulations cover even more types of transactions, but we’ll explain more on that below.

Three main federal agencies administer the U.S. export controls regulations. They are listed below in the order of sensitivity relative to national security and foreign policy. Essentially, the potential fines and penalties for violations increase as you go down this list.

- Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS): Export Administration Regulations (EAR)

- Department of State’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC): International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR)

- Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets and Control (OFAC): Foreign Assets Control Regulations (FACR)

There are a few commonalities between these agencies and many differences. Fundamentally, they all have a framework for authorizing (or pre-authorizing) certain exports of tangible items, software, technology, and, in some cases, services as well. The concept of providing authorization comes from issuing a license to applicants requesting permission for an export or deemed export. All of them expect the exporting party to have an internal management plan, often referred to as Technology Control Plan, in the case of deemed exports.

Each agency above maintains its own list of restricted or denied parties. Parties can be universities, companies, individuals, or other groups/entities. In most cases, exporting items from the U.S. to entities captured on any of these “restricted party lists” demands meeting heavy licensing or other requirements.

Beyond this, the differences between the EAR, ITAR, and OFAC sanctions regulations are important to understand. We’ll point out three of the major distinctions.

The EAR and ITAR contain extensive lists of sensitive items that those agencies regulate. A key difference is that the impact of the “export controls lists” varies under each set of regulations. In the case of the Department of Commerce, the licensing requirements connect back to detailed numbers on the Commerce Control List (CCL). It contains specific export control classification numbers (ECCNs) that describe certain tangible items, technology, or software. In most cases, the licensing requirements will connect to the ECCN of the exported item. While the Department of State has its list of sensitive items, called the United States Munitions List (USML), the precise number (“Category”) on the USML does not impact the licensing decision. Anything listed on the USML will require a DDTC license for all non-U.S. Persons to access.

A second difference is that the ITAR and the OFAC regulations cover “services,” while the EAR does not strictly regulate services.

Lastly, the OFAC regulations are focused on the destination country and the overall nature of the transaction. The licensing framework is not driven by what is being shared or shipped, but rather, which country is receiving it. Certain destinations have more comprehensive sanctions against them (e.g., Iran), and thus, licenses are harder to obtain. Some countries bring on steep restrictions even though they are not comprehensively sanctioned (e.g., China and Russia). The key countries of concern are:

- Iran

- Cuba

- Syria

- North Korea

- Certain Regions of Ukraine

How does this translate into university export compliance needs? The key elements of an Export Compliance Program at a university span a broad range of administrative offices. In a comprehensive compliance program, export compliance “steps” or aspects should exist in all the below operations. Furthermore, restricted party screeningprocesses should be incorporated into nearly all of them. The exact processes or procedures will vary across institutions due to the differences in basic operations. However, it’s important to establish standard processes.

- Sponsored research screening process

- Immigration/visas process

- Visitors screening process

- International shipping process

- International travel process, in conjunction with IT protocols

- Procurement processes

- IT policies and processes

How are universities faring when it comes to handling all these decentralized needs? A recent government study provides some insight for university auditors.

GAO Report for University Export Controls

In May 2020, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) concluded a study of export compliance at U.S. Universities. The resulting report recognized the complexity of managing export controls in an academic setting and called for heightened clarity and guidance from the federal government. This section may serve university auditors by indicating key areas of focus for future audits.

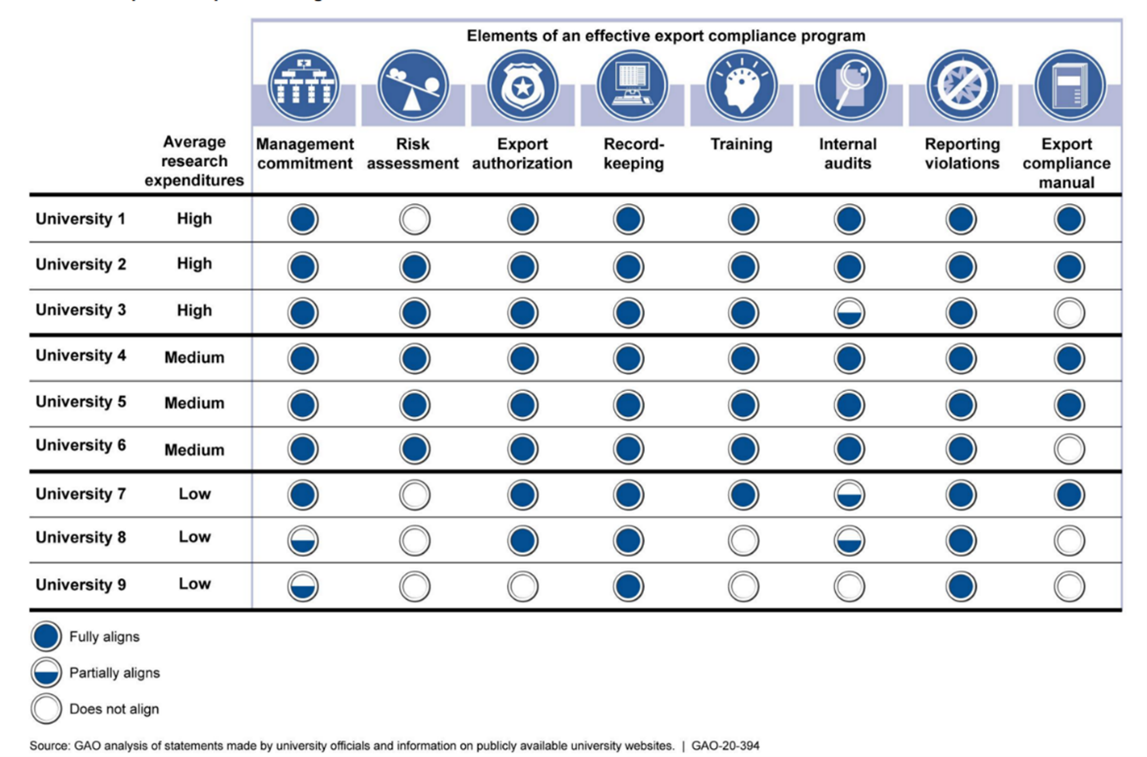

The report, “State and Commerce Should Improve Guidance and Outreach to Address University-Specific Compliance Issues” (GAO 20-394), expressed concerns about undue foreign influence on universities and personnel. The study evaluated the management of export controls at nine universities. These anonymous institutions were sorted into three groups, those with high average research expenditures, a medium expenditures group, and universities with comparatively low research expenditures. The report concluded with four recommendations to the Departments of State, Commerce, and Defense to heighten clarity and improve guidance to institutions.

The following chart provides a summary of the GAO study findings.

Overall, GAO discovered that export controls were more fully implemented at universities with higher research expenditures, which aligns with the relatively greater risks faced at these institutions. Of the eight areas examined by the GAO, nearly all the universities visited were aligned with the requirements of four topics: management commitment, export authorization, recordkeeping, and reporting violations. In this article, the authors emphasized four areas with the most room for improvement, as was done during the corresponding panel presentation at AuditCon 2022. These areas are risk assessment, training, internal audits, and export compliance manual.

Four of the nine universities visited by GAO had not conducted risk assessments. A risk-based approach can empower an institution to address areas of greatest concern. Yet, export controls impact many activities at an academic institution, and the day-to-day demands can be so great that it is challenging to conduct such an assessment. GAO called for additional clarity from the Department of State, whose new guidance is anticipated by the end of 2022.

GAO examined two elements of export control training programs: 1) whether suitable training was available and 2) whether training was mandatory for the appropriate employees. One could argue that training is the heart of any compliance program. Although the majority of universities visited were in alignment, GAO found that two universities were not aligned with this requirement.

Quite possibly, internal audits are the area of greatest interest for the reader of this article, and indeed this was one of the four areas in greatest need of attention, according to the GAO report. Only five of the nine universities visited met the standard, with the remaining four either partially or not yet aligned with this goal.

Finally, of the four areas evaluated by GAO, nearly half of the universities visited had not created an export control manual. Not only is such a manual essential for managing an effective compliance program, but it is also the basis for an audit of that program.

Design & Implementation of an Internal Audit for Export Controls: Scope & Tips

Scope of a University Export Control Program Internal Audit

The scope depends on the individual export control program. An internal audit may result from an export violation or best practice in compliance. A good place to start is by reviewing the export control program guidance from the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS)[1], the State Department’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC)[2], and the Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)[3] to see if your export control program contains all the required elements. The guidance documents outline the three agencies’ basic requirements for industry and college and university export control programs. All three agencies require audits as an effective export compliance program element. If your export program is missing an essential program element(s), you already have a recommended place to begin.

An internal audit of an entire university export control program will be overwhelming in scope. It is not recommended because export control programs are governed by multiple federal agencies and regulations and overlap with many university functions (e.g., international travel, international shipping, sponsored research, hosting and hiring international employees and scholars, etc.). However, a comprehensive gap analysis of your export control program may help determine the focus of an internal audit. The export control program, internal audit, or an outside consultant may handle a gap analysis. Internal audit will be unbiased, while export control will have more substantive knowledge. An outside consultant may have substantive knowledge but will require additional resources.

The scope of an internal audit may be limited to one federal agency’s regulations, such as the export administration regulations (EAR)[4] under the Commerce Department BIS or to a specific area of the program, such as international shipping, international travel, technology control plans (TCPs), hosting and hiring international visitors and employees, etc. The internal audit may focus on how restricted party screening is handled by the export program as a whole or for a specific area such as international shipping. An internal audit’s focus may be limited to online graduate programs and how a university complies with the OFAC sanctions’ prohibition against providing a “service” to comprehensively sanctioned countries (including online education).

Approach to University Audits

The BIS “Export Compliance Guidelines, The Elements of an Effective Export Compliance Program” requires eight (8) elements: 1. Management commitment, 2. Risk assessment, 3. Export authorization, 4. Recordkeeping, 5. Training, 6. Audits, 7. Handling export violations and taking corrective actions, and 8. Build and Maintain your Export Compliance Manual. This is a good framework to start with when determining the best approach for a university audit. [5]

Many campus compliance business areas overlap with export control and trade compliance; (e.g. hosting J-1 Exchange visitors {Bridge USA Program} overlaps with export compliance and Procurement and Accounts Payable overlap with international purchases (imports)). An internal audit may only cover a separate business area and not the overlapping export and trade compliance concerns. However, the results of the internal audit may also impact export compliance. The export compliance program can highlight the risks found and advocate for additional resources to mitigate those risks, such as additional dedicated staff and training. The scope and approach depend on the reasons for the audit and the specifics of the individual export control program and college or university.

Frequency and Content of Audits

BIS, DDTC, and OFAC require audits in their export control program requirements.[6] These program audits may be conducted by the export control program (self-reviews), internal audit, or an outside auditor/consultant. The federal agencies do not specify who is to conduct the audits. The requirement is to make audits an essential element of export control programs to identify risks and compliance gaps and implement the mitigation. Federal agencies recommend the mitigation strategy is audited within one year to ensure it is effective[7]. BIS’ guidance specifically indicates, “[i]f resources allow, it is a good business practice to periodically utilize an outside auditor.”[8] The federal agencies do not specify or mandate who conducts the audits but rather require audits to make sure export control programs are continually reviewing the program annually to find compliance gaps and improve the program. These federal recommendations can serve as a basis for securing leadership buy-in for getting started with your first audit.

An export control compliance program may have internal audits periodically for specific areas of the program and the export control program staff may audit other areas annually. Technology Control Plans (TCPs) for sponsored research, for example, can have four annual audit requirements:

- Are there any changes in the scope of the work performed that require a change to the TCP?

- Are there changes in who is working on the project? (PIs need to contact the program to have new personnel read and sign the TCP and attend export control training before beginning work per the TCP.)

- Are there any changes in the physical location where the work is performed?

- Perform a new physical inspection annually.

In addition, internal audit may audit the entire TCP process above and provide recommendations and mitigation strategies.

Benefits of Internal Audits

Auditing an export controls compliance program is a relatively new endeavor for many internal audit teams at universities. In fact, many institutions are still building out their initial export controls compliance program. Thus, internal audits can help frame what is going well and identify opportunities for improvement. Budget issues at colleges and universities are real, so an audit highlighting the need for additional staff and new tools has proven to be valuable at certain institutions. Audits can also highlight where export control programs overlap with other areas and recommend increased collaboration to eliminate silos on campus to increase compliance.

References

- https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/pdfs/1641-ecp/file

- https://www.pmddtc.state.gov/sys_attachment.do?sys_id=35c9a068db995f00d0a370131f9619bb (for download)

- https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/framework_ofac_cc.pdf

- https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/regulations/export-administration-regulations-ear

- Ibid 1.

- Ibid 1-3.

- Ibid 1.

- https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/pdfs/1641-ecp/file, page 30.