An effective control environment is all about culture, ethical values, and appropriate governance structures. This includes attracting and retaining individuals whose values align with those of the organization and holding them accountable for their actions. It is about setting the norms for how members of an organization agree to treat each other, uphold policies, and deliver on the mission and strategy of the organization.

Culture drives behavior and underpins success or failure of any team. In the best of times, it is difficult to create and protect. Building a strong culture is a meticulous task that requires continuous focus and dedication. Within every interaction lies an opportunity to reinforce culture. Strong connections between people create a higher sense of accountability and responsibility. That is precisely why auditors should always consider cultural aspects of an organization in their engagements.

The Ripples of the Pandemic

In higher education, we operate in a world of multi-faceted operations, shared governance, and federated control structures. Even on a good day, it is challenging to bring the relevant parties to the table to lead conversations about internal controls, fraud risks, and policy governance. Add to the mix the historically poorly documented practices (because someone “has been in their role for many years and they know what they’re doing”), turnover brought on by the great resignation, and the inherently complex and ever-changing compliance and operations landscape, and you have a perfect recipe for the heightened risk of unintentional or intentional misapplication of policies and procedures that may lead to financial or reputational damage to our institutions.

While nearly all core university operations are back on campus in full swing, support operations, such as accounting, finance, information technology, and yes, internal audit, have a varied degree of presence. And while we all have grown to appreciate the flexibility, especially when needing to take care of children, elderly parents, or pets, I can’t help but wonder what might auditors be missing by not being in closer physical proximity with our stakeholders. What has been the impact of multiple work modalities on an organization’s ability to keep focused efforts on compliance and maintaining an effective control environment, particularly in a space as complex and distributed as higher education? If culture truly is the single biggest determinant of employee behavior and organizational success, how can it be cultivated, maintained, and shared, with some employees never having set foot on campus? If there isn’t an intentional effort to create that focus, what is the impact on fraud risk?

The cost of fraud extends well beyond the actual loss suffered. It leads to additional time and money invested in investigations, pursuing actions against perpetrators, and remediating control weaknesses. Fraud also causes a decrease in employee confidence and morale, loss of productivity, and the decline in institutional reputation and degree value. The list of fraud victims at institutions is broad: research sponsors, donors, alumni, current and prospective students, faculty, staff, and larger communities.

With the ripples of the pandemic, we went from knowing and conversing with our office neighbors to working in near isolation. Not many leaders thought of preserving culture as they scrambled to keep core operations on track, getting creative about adapting processes to the new realities. When not actively and intentionally cultivated, culture fades, as do relationships and accountability.

And that is where auditors need to pay attention. Auditing culture is hard, complex, sensitive, politically charged, often subjective, and, let’s be honest, frustrating. But that doesn’t mean we can’t be alert to the associated risks and incorporate them in our engagements.

No Longer Business as Usual

The post-pandemic working modalities have added new risks and opportunities to organizations. With increased turnover, there was a loss of institutional knowledge. With less tenured staff, or less staff period, there was an actual or a perceived lessoning of oversight. As staff were re-thinking their priorities, so were the students. With enrollment numbers fluctuating and the federal and state support weaning, institutions began to experience budgetary pressures. Faculty and staff were taking on additional responsibilities, which, coupled with higher turnover and overall uncertainty, led to burnout. It became a lot easier to rationalize circumventing controls when feeling overworked, underpaid, and doing the job of several people. Along with a lack of feeling connected to the organization, the risk of unnoticed mistakes and fraud increased.

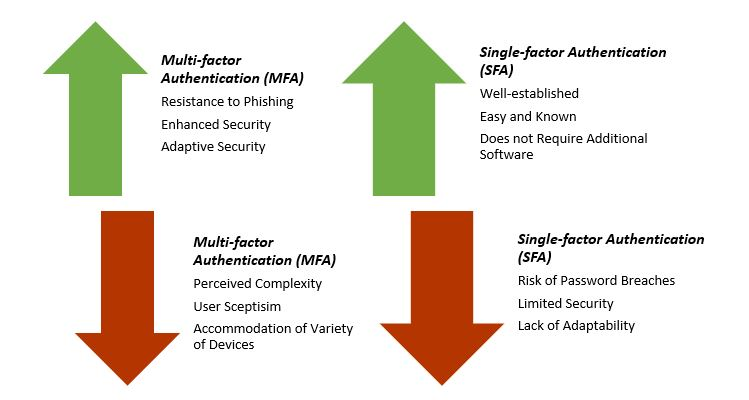

Trust is Not a Control

Trust helps organizations thrive and achieve goals with greater efficiency. It is an imperative ingredient for healthy relationships and operational effectiveness. However, it does not replace strong internal controls that are tailored, documented, and tested. During the pandemic, many core processes were adjusted for the needs of the times. In some cases, those changes created efficiencies that would stand the test of time, while in other cases controls may have been over-simplified, leading to design weaknesses in the post-pandemic space. Now is an excellent opportunity for auditors to help their organizations evaluate which changes have the staying power and which ones need to be reverted or reconsidered to ensure a strong control environment.

Auditors must possess curiosity, critical thinking, and connectedness with the organization and its culture. Audit planning is the ideal time to understand what has changed in the organization in terms of leadership priorities and risks to help create a more relevant scope and objectives for the audit. The audit universe should be reviewed periodically to identify changes that affect culture and help keep the internal audit function stay systematic and organized.

Auditors should not underestimate the power of a relationship with stakeholders. The quality of those relationships should be cultivated over time. Every interaction can be an opportunity to establish trust in the audit process and provide comfort to stakeholders that they will be supported by Internal Audit with utmost professionalism at the time of need. Auditors should remember to listen with intent to the insights the stakeholder may want to share about departmental changes and cultural shifts.

Culture Matters

Incorporating cultural factors into audit work can enrich perspectives on the organizational control environment. Here are just a few examples of questions to consider:

Tone at the top:

- Does leadership set realistic performance targets and communicate them consistently and clearly across the organization?

- How is organizational culture shared with fully remote employees? How is their sense of belonging fostered?

- Has the institution performed a climate and culture survey after the pandemic? What were the trends and action items?

Employee services processes:

- Does your institution consider ethics and integrity of candidates in the hiring process?

- Does your institution’s philosophy on performance management reflect its values and creates an environment of accountability, integrity, and respect?

- Is success enabled through periodic training and documented performance guidelines and expectations?

- Are core hiring processes which may have been simplified during the pandemic, being executed with sufficient law and policy compliance? This includes background checks, I-9 reviews, salary change approvals, vacancy postings, etc.

Reporting mechanisms:

- Are reporting mechanisms, such as a hotline, implemented and effective?

- What has been the volume trend for the hotline in the past three years? Is there a change in the types or number of allegations reported? Are the allegations being investigated and resolved?

Business processes:

- Are internal controls designed for new work modalities?

- Are policies relatable, enforceable, simple, and easy to use?

- Have cash management controls reverted back to pre-pandemic standards? Cash management controls may have been adapted during the pandemic, with no one in the office to receive checks, make deposits, or allow for sufficient segregation of duties.

- Have procurement purchasing cards been adequately monitored? Were higher approval thresholds or looser controls adopted to cope with procurement shortages?

- Are conflict of interest processes robust enough to educate reporters on what should be disclosed and provide the appropriate level of information for review of possible issues? Are the mitigating plans consistently established, monitored, and enforced?

Next Steps

Due to today’s high pace of macro-environmental changes, multiple work modalities, and continued impacts of the pandemic effects, sustained attention to organizational culture remains critical for effective mitigation of financial, ethical, and compliance risk. Internal auditors can play a vital role in educating their organizations about effective internal controls. There is value in reminding business leaders that trust is not a control, and that they play an important role in establishing the right combination of mechanisms, rules, and procedures to ensure the integrity of information, promoting accountability, and preventing fraud.

If there is one thing we learned in the last four years, it is that change is a constant. Internal auditors can support their institutions attain their goals and objectives by periodically re-evaluating the control design for continued appropriateness. Although internal auditors may not be experts in every process they review, they are experts in validating the design and effectiveness of internal controls. Considering cultural nuances when planning and executing internal audit engagements will only amplify their value.