Facilities Management Inventory

Higher education institutions are routinely engaged with the construction of new capital projects. The significant investments will likely necessitate routine internal audits to ensure funds are being expended appropriately. On campuses with multiple projects, the initial challenge is determining which project(s) to review. This article provides a primer to embarking on a construction audit when you have a limited background (at best) in construction by addressing the following items:

Construction is delivered under multiple approaches, often called “delivery methods.” The construction contract is tailored to the delivery method being employed on the project in question. Common delivery methods include Design-Bid-Build, Multi-Prime, Design-Build, Construction Manager-at-Risk, and Integrated Project Delivery.

The most common construction delivery methods in higher education today are Design-Bid-Build and Construction Manager-at-Risk. Design-Bid-Build contracts are commonly referred to as “hard bid” or “lump sum”. These projects are completed for a fixed price and are often used on smaller projects where drawings are complete and the scope has been finalized. Given the reduced risk from a financial perspective, the scope of an audit would be primarily focused on any change orders.

Larger projects are often built utilizing a Construction Manager-at-Risk delivery method. This method engages the construction manager prior to final drawings in order to leverage their expertise with constructability reviews at various stages of design. This approach utilizes a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) contract. This contract segments the recovery of project costs into the following components:

The GMP contract establishes a cap for the amount paid for the construction, but allows the project owner to retain any variance should the GMP exceed the total realized project costs. As a result, GMP contracts generally have more areas of potential audit exposure from a financial perspective. With resources often being limited, audits of construction in higher education naturally gravitate to GMP contracts given their compensation terms and greater project values.

(For the purpose of this and the remaining steps, it is assumed a GMP contract is being reviewed)

Once the project(s) to audit has been selected, the Auditor will need to develop an initial documentation request to obtain the following items:

Requests sent to the Contractor should be directed to the Project Executive and/or Project Manager. The construction contract should then be reviewed, specifically sections addressing the “costs to be reimbursed” and the “costs not to be reimbursed.” The compensation terms should detail the usage of pre-determined rates and actual costs. Additionally, the contract should specify the overhead items covered by the Contractor’s fee.

A source documentation request should then be sent by the Auditor to the Contractor’s Project Executive and/or Project Manager for multiple items:

The lowest source document should be determined for the request. For example, the original timesheet should be requested to validate the hours worked by an employee. These lowest source documents are utilized to create the monthly project billings and provide valuable insight often lost if reports are created specifically to satisfy audit requirements. These documents often contain commentary and details about transactions later adjusted and/or ‘corrected’. In some cases, the source document can further demonstrate how a transaction has been ‘cleaned’ to avoid scrutiny during the payment approval process.

The contract should specify whether labor is to be billed at pre-determined bill rates or actual cost plus burden. To effectively review labor costs utilizing bill rates, timekeeping records should be requested. To the extent the contract does not explicitly specify the bill rate components, the Contractor should be requested to provide them. Bill rates routinely include paid time off, benefits, base wages, payroll taxes and unemployment insurance.

Labor billed at actual cost plus burden will require payroll records, including employee deductions and timekeeping records. To the extent the contract does not explicitly specify the burden components, the Contractor should be requested to provide them. Burden rates are applied to base wages and routinely include paid time off, benefits, payroll taxes and unemployment insurance.

If the contract does not specify the use of pre-determined bill or labor burden rates, the labor is normally reimbursed at actual cost plus actual burden. The audit will need to independently estimate the cost of the labor burden. Documents needed to complete this estimate include:

Contractors may lease their owned equipment to the project. The contract language often specifies these rental rates are to be indexed to a third-party source, such as the AED Green Book or EquipmentWatch Blue Book. The contract language may specify the lease rates are to be indexed at less than 100% to the index in question. Additionally, the language may specify when lease payments are to cease. If not, the fair market value or replacement value is the

implied point when payments should cease. The Contractor should be requested to provide a leased equipment summary, inclusive of the following items:

The construction contract should specify the various insurance coverages required by the contract. The most common coverages, and their means of compensation, are as follows:

General Liability Insurance will often be charged at a rate that may or may not be defined in the contract. If the rate is not specified in the contract, request a breakdown of the rate charged to the project. The rate breakdown provided should be analyzed to determine if it includes coverage not required and/or if overhead has been included. The project requirements for policy coverage and limits should be located in the Contract agreement. The Auditor should verify the coverage and appropriate limits have been obtained by requesting a Certificate of Insurance from the Contractor which lists the project owner as the named insured for the project in question.

Builder’s Risk Insurance and Performance and Payment Bonds are usually purchased specifically for the project. An invoice should be requested to document the purchase. The vendor providing the invoice should be confirmed to be an independent third party, as captive insurers are often used, reducing the transparency of the actual cost incurred.

Subcontractor Default Insurance is routinely charged at a rate specified in the contract. This rate is applied to the combined subcontract values enrolled in the program. To confirm the amount charged, a list of enrolled subcontracts should be requested. The Schedule of Values in each subcontractor payment application should then be separately scrutinized for the inclusion of bond costs. If identified, this is most likely a duplicate charge to the Subcontractor Default Insurance.

IT expenditures are often allocated and charged to project costs by Contractors. Contracts may allow for “project-specific” IT expenditures such as laptop computers, internet connectivity, and on-site support. Correspondingly, contracts normally disallow corporate overhead IT expenditures (accounting systems, home office servers, and home office support). The contract language related to IT, however, is usually nebulous. As a “rule of thumb,” if the IT item is utilized on-site, it’s likely permissible, but if utilized in a home office, it is likely overhead and should not be billed. Invoices should be provided for all IT charges without contract language specifying an IT rate. This approach is the most transparent from an audit perspective. As with the insurance, the Auditor should be wary of any IT invoices from a related party. Any computers and other hardware charged to the project should revert to Owner control at the project’s end. To the extent an IT rate is specified in the contract, the project cost report should be scrutinized to ensure IT charges covered by the rate have not been direct billed to the project. If the IT rate’s components are not defined, the Contractor should be requested to provide them.

A retrospective review of project change orders will require copies of fully supported Owner Change Orders, which are the summation of multiple change requests made to the project owner for approval. The support should include a cover sheet with an itemized list of the change order items. The subcontractor support for each individual change order should then follow, and this support should then be reconciled to the cover sheet. The Contractor’s markups for insurance, overhead, and profit should be present on the cover sheet and should be confirmed against Contract stipulations. The markups applied on Change Orders should be validated for the following:

In addition to markups, the Change Order review focuses on these items:

The project cost report provided in the initial document request should be sorted to segment transactions not falling into labor, equipment, subcontracts, insurance, and information technology categories. Most of these charges will be for vendors paid via purchase orders. The transactions should be further segmented into a list where the reimbursable basis cannot be readily determined – these invoices should then be requested from the Contractor. The invoice review should focus on the following items:

Journal entries may comprise the remaining transactions, and backup should be requested for any that are questionable.

Auditing construction costs may seem like an impossible task without specific expertise and limited resources. However, focusing your audit program on projects with contracting terms with more material financial exposure is the first step in developing an effective review of these capital expenditures. Following project selection with targeted documentation requests will allow the development of an effective and efficient process for reviewing construction project costs.

The construction industry has historically been a slow adopter of technology, and rightfully so. The builders of our roads, homes, offices, and campuses need to be thoughtful when evaluating new technology that may impact safety and quality in exchange for speed and cost reduction. Consequently, the introduction of robotics, video monitoring, and automated quality controls has trailed behind other industries, such as manufacturing and distribution. Similarly, as the availability of digital information has increased, the implementation of automated construction audit techniques has lagged. However, high speed wireless communication, handheld devices, and a need for labor force alternatives continues to drive construction technology innovation and adoption. Construction auditors must remain knowledgeable with the latest industry tools and understand how to evaluate new construction technologies’ impact on construction risk management.

The most established technological advancements, such as GPS-enabled cranes and heavy/highway equipment with onboard performance metrics, enable operators to cut, grade, and measure moved earth with a high degree of precision. The equipment can be monitored remotely, which allows companies to track their exact location, operating hours, consumables, and environmental conditions. The existence of this data also provides information for construction audits. Rather than analyzing paper copies of supporting documentation, construction auditors may now utilize available digital technology to download equipment metrics and capture quantities moved, hours operated, and other pertinent equipment usage data quickly.

Rather than analyzing paper copies of supporting documentation, construction auditors may now utilize available digital technology to download equipment metrics.

A large campus transformation project may include new buildings, new roads, and new underground infrastructure. This would require moving large amounts of dirt and parking contractor equipment at the jobsite, resulting in monthly bills for dirt hauling, aggregate purchases, and heavy equipment rental. To determine whether the quantities billed are representative of actual activity, an engineer could measure the dimensions of the dirt (i.e., how high and wide the dirt sits) to calculate the quantities moved.

Alternatively, the auditor could download the operating metrics from any cloud storage application to see the number of dump trucks that were on site, the trips each truck made, the weight of the product hauled, and the time spent loading and unloading. The auditor could then calculate cubic yards moved from the site to reconcile the trucking bill. A similar reconciliation could be performed using operating hours, GPS coordinates, and performance metrics from earthmoving equipment.

In addition, there are other methods of construction automation. One example is modular construction, which is an effective alternative to on-site construction methods. Modular construction is a process, in which a building constructed off-site under controlled plant conditions, uses the same raw materials as conventionally built facilities, and adheres to the same industry codes and standards—in about half the time. Buildings are produced in “modules,” which when put together on-site, reflect the identical design intent and specifications of the most sophisticated site-built facility. Furthermore, controlled plant conditions enable the contractor to leverage trade and craft automation to build walls, assemble plumbing, and fabricate ductwork.

Modular construction automation leads to the following areas of note:

Data collection is an area that has experienced great advancement the last few years. Two areas that benefit from construction audits include employee tracking and direct labor hour collection. Historically, timesheet collection was a manual process and often the burden of the superintendent on the construction project. Now, mobile phone applications allow individual employees to enter their time and automatically forward their timesheet to the superintendent for approval. Once approved, the labor cost will post to the job cost ledger. In addition, large multi-disciplined projects are implementing wireless jobsite worker tracking. The employee enters through a control gate and swipes an identification card or wears a radio-frequency identification (RFID) badge, which captures physical jobsite location and enables the contractor to know, at any given time, who is on the jobsite and their location. The construction auditor may use this data to verify personnel and the number of hours worked on the jobsite. By reconciling this jobsite data with timesheet data and physical locations, timesheet errors can be detected and worker productivity can be audited.

As automated and digital data collection becomes more prominent, it will be necessary to place greater reliance on project controls to detect fraudulent or abusive behaviors.

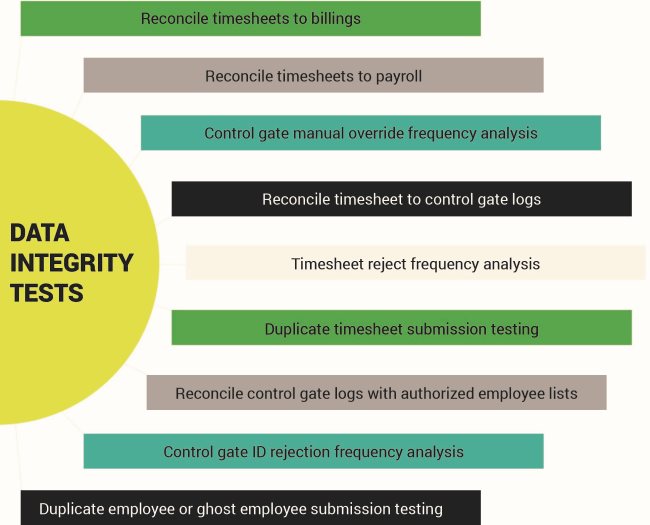

As automated and digital data collection becomes more prominent, it will be necessary to place greater reliance on project controls to detect fraudulent or abusive behaviors. Auditors should thoroughly test the project controls before relying on these systems to generate accurate source transactions. Comprehensive audit programs should include project controls testing that include employee identification card issuance and replacement, timesheet rejection processes, rejection frequency tracking, and payroll-to-job cost adjustment reconciliations. In addition, audit programs should also include data integrity testing to gain assurance that the data collection and reporting systems are functioning as intended. The graphic shown below highlights some common data integrity tests.

Previously, construction audits often experienced roadblocks due to the inaccessibility of information. Today’s automation systems are digitizing source documents; therefore, enabling a more comprehensive testing at a lower cost per transaction tested. While this may provide an opportunity for more automated audit procedures, the audit methodology does not change.

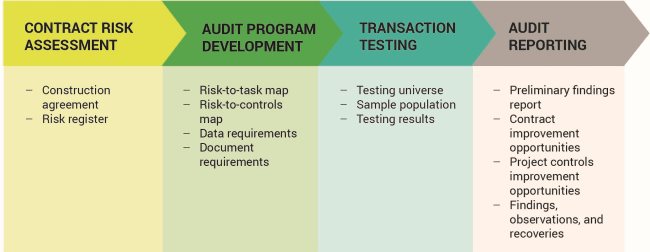

Each phase of the methodology benefits from technological advancements and automation.

This phase includes a technical review of the contract terms and conditions. By applying any past risk assessment experience, the contract terms are equated with known risks. For example, the cost of work requires labor burdens to be billed and reimbursed at cost, without additional markup. Some associated risks with labor billed in excess of cost may include inflated labor burden, duplicate benefit hours, or embedded profit. Business intelligence software now allows auditors to compile a database of past contract observations, and when paired with optical recognition software, a contract can be scanned and then the contract terms are mapped to known risks. The results produce a system generated preliminary contract risk analysis, which significantly reduces the amount of time to perform this same task manually.

Contract risks are mapped to a series of audit steps, allowing business intelligence software to then produce a draft audit program based on the associated contract risks. The database maintains the data requirements for the audit program and associated supporting documentation requirements, which is then provided to the contractor and owner so the audit can proceed.

Many transaction tests and reconciliations can be automated, which eliminates redundant data handling and relevant constraints on construction audit progress. Regardless of whether an auditor has a fully integrated business intelligence solution that can perform the testing, experience is still required to interpret the data, evaluate results, and assess whether new scenarios exist that were not addressed within the automated testing environment.

With the increases in the level of automation, auditors’ responsibilities grow significantly.

With the increases in the level of automation, auditors’ responsibilities grow significantly—whether it is an increase in testing or placing a greater emphasis on project controls interviews, control effectiveness, and results interpretation to mitigate construction project risk. Automation allows an increase in sample size and overall testing populations, which allows auditors to get better coverage and have more detailed findings.

Despite all the advances in technology that impact the construction industry, the audit solution is only as good as the subject matter experts that assess the contract risks and develop audit programs. Auditors will be needed regardless of the level of automation and should not be concerned about automation eliminating their jobs.