New Global Internal Audit Standards Released

New Consolidated Structure

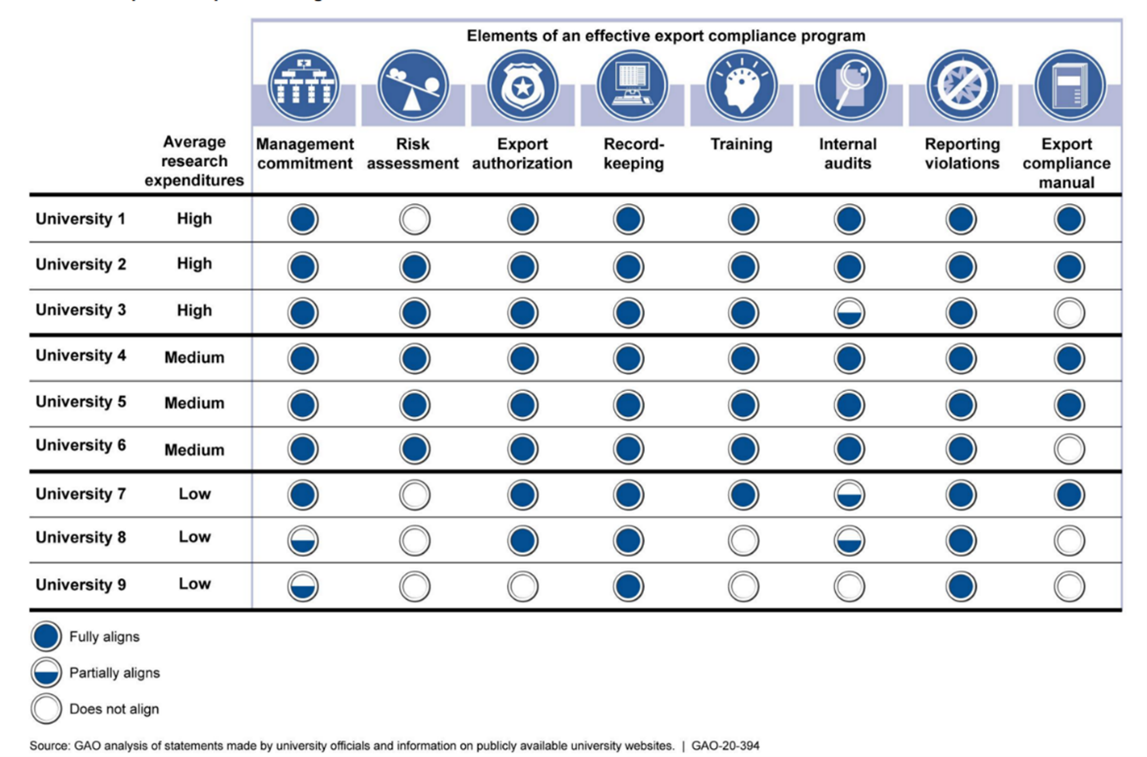

On January 9, 2024, the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) released their updated Global Internal Audit Standards, which will become effective on January 9, 2025. The ACUA Auditing & Accounting Principles (AAP) Subcommittee advocated for ACUA members during the comment period and recently presented the changes at the 2024 ACUA Virtual Spring Summit.

The prior International Professional Practices Framework (IPPF), published in 2017, was decentralized into four different documents: the Standards, Code of Ethics, Core Principles, and the Definition of Internal Auditing. The new IPPF is one single 120-page document comprising of five domains, 15 principles, and 52 standards. Each standard has its own requirements, considerations for implementation, and examples of evidence of conformance. Additional guidance in the form of Topical Requirements is forthcoming.

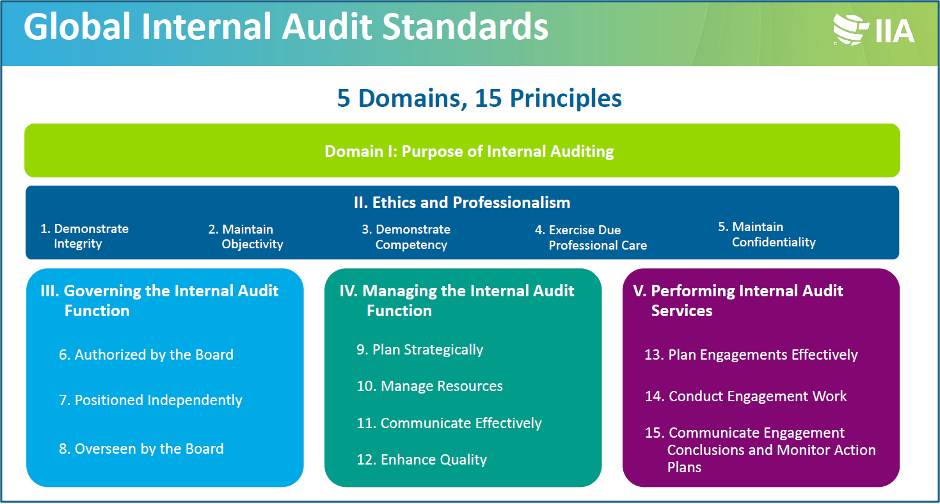

Structure of the International Professional Practices Framework, slide courtesy of the IIA.

The Five Domains

The new Standards are now organized into five logical domains that contain the 15 key principles. During the public comment period, most respondents appreciated the organization of the new domains.

The Global Internal Audit Standards five domains, slide courtesy of the IIA.

- Domain I: Purpose of Internal Auditing updates the purpose and describes how internal auditing enhances the organization and when it is most effective. The new purpose statement reads “Internal auditing strengthens the organization’s ability to create, protect, and sustain value by providing the board and management with independent, risk-based, and objective assurance, advice, insight, and foresight.”

- Domain II: Ethics and Professionalism embodies the former Code of Ethics’ principles of integrity, objectivity, confidentiality, and competency, and adds maintaining confidentiality.

- Domain III: Governing the Internal Audit Function includes “essential conditions” for an effective internal audit function, including organizational independence, internal audit charters, Board interaction, resources and support, plus external quality assessment.

- Domain IV: Managing the Internal Audit Function describes Chief Audit Executive functions including departmental planning, managing resources, communicating, and performance measurement.

- Domain V: Performing Internal Audit Services provides guidance on conducting engagements including planning, analysis, reporting, and confirming the implementation of action plans.

Major Changes

Overall, the biggest change to the new Standards is the consolidation and regrouping of topics. There is a new emphasis on serving the public interest and being able to apply the Standards to the public sector. The most significant changes include:

- No more differentiation between assurance and consulting engagements. The Standards apply to all engagements.

- There are new “essential conditions” in each of the nine standards in Domain III describing the appropriate governance arrangements essential for the internal audit function to be effective, which strengthens the importance of Board relations.

- The Standards have become more prescriptive throughout. Recommendations that were previously labeled as “consider” or “should” have turned into “must.”

- There is a greater emphasis on strategy, relationship building, and communication in the Management domain, along with new emphasis on internal audit performance measurement.

- There is additional emphasis on performance management, where the CAE must develop performance measurement criteria and assess progress towards achieving the function’s objectives while promoting continuous improvement.

- The final communication must include an engagement conclusion that summarizes the engagement results, and individual engagement findings must be prioritized based on significance but do not require rankings.

- For external quality assessment reviews, at least one independent assessor must hold a Certified Internal Auditor (CIA) designation.

Topical Requirements

The IIA intends to release several Topical Requirements, which will cover aspects of governance, risk management, and control processes and include considerations related to a specific topic. This guidance will be required when auditing an area covered by a Topical Requirement. To date, the IIA has released a draft of their Topical Requirement on cybersecurity, which is for public comment through July 3, 2024. Please visit the IIA website to read the draft and make any comments. Other topics under consideration include sustainability, third-party management, IT governance, assessing organizational governance, fraud risk management, privacy risk management, and public sector performance audits.

ACUA’s Top Concerns

During the public comment period, the AAP polled the ACUA membership about their reaction to the proposed changes. Members appreciated the new organization, format, and clarification of roles and responsibilities of the internal auditors versus the Board, along with the de-emphasis on assurance versus consulting. Using membership feedback, ACUA President Melissa Hall formally responded on behalf of ACUA on May 31, 2023. In addition to the above-noted items of appreciation, this response also included top concerns, including the overly prescriptive nature of the Standards and its potential burden on smaller internal audit functions. The IIA considered the public comments and revised the draft Standards prior to publishing.

This is how the IIA addressed the top three ACUA concerns:

- Domain III: Governance – ACUA members were concerned that the Standards pertaining to the Board were outside the control of the CAE. The final Standards focused on the CAE’s responsibilities and how the CAE can assist and inform the Board of their responsibilities.

- Standard 8.4 External Quality Assurance – ACUA members were concerned the proposed Standards required external quality reviews be led by a CIA, and all team members needed to successfully complete an IIA training course. The final Standard does not require completion of an IIA course by external assessment team members, and only one team member (and not the lead) must hold the CIA designation. Also, the final Standards allows for self-assessment with independent validation.

- Standard 15.1 Final Engagement Communication – The proposed Standard required findings be “ranked by significance,” generating concerns audit clients would be too focused on subjective rankings and unnecessary conflict between the internal audit function and management would ensue. The IIA removed the requirement to rank findings, instead requiring the final report include the significance and prioritization of the findings.

Implementation Next Steps

The ACUA AAP Subcommittee recommends the following next steps in your institution’s journey to the January 2025 implementation effective date:

- Get familiar with the new Standards.

- Start to develop a plan for implementation.

- Communicate these changes with your senior leadership and Board.

- Update the internal audit function’s strategy “that supports the strategic objectives and success of the organization and aligns with the expectations of the board, senior management, and other key stakeholders.”

- Update or create performance metrics and plan how to measure those metrics.

Consider performing an internal assessment using the new Standards this year and implement any changes prior to the January 2025 effective date. If your External Quality Assessment is due in 2025, consider completing it in 2024 before the Standards change and the CIA on the review team is a requirement. If your internal audit function is not conforming with all of the new standards by January 9, 2025, you must remove the phrase from audit deliverables indicating your engagement was performed in accordance with the Standards.

If you are considering becoming a Certified Internal Auditor, the IIA states there will not be any changes to the CIA exam before May 2025. The IIA plans on communicating any changes at least one year in advance and new study materials are not expected to be released before March 2025. Those candidates in-process will receive detailed information. In addition, there will be no changes to the Internal Audit Practitioner designation before the effective date, and the Certification in Risk Management Assurance (CRMA) exam is not affected by the changes.